The Latter Day Followers of Leon Trotsky

Those seeking to change the way society is organized will at some stage come across a fractured group of people with ideas about it. They are quite active and visible, though perhaps not so much as they once were. Demonstrations and picket-lines, selling papers at universities and outside tube stations is their stock-in-trade. These days they are not in the best of health and struggle to make the impact they once did. They are the followers of Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky.

Trotsky played a significant role in the 1917 Bolshevik takeover in Russia led by Lenin, but after Lenin’s death was squeezed out by his successor Josef Stalin, went into exile in Mexico and then was murdered there by Stalin’s agents in 1940. It is perhaps a little odd that his modern acolytes are as well-known and persistent as they are. Not unlike the splintered religious sects that offer a regimen of activity and surety of doctrine, with each one microscopically different to the other.

A new book by John Kelly called Contemporary Trotskyism (Routledge, 2018) has set out to examine this phenomenon. Perhaps surprisingly, it is the first book-length analysis of the Trotskyist movement in Britain for over 30 years. It is meticulously researched and packed with detail. ‘Left-wing train-spotters’ everywhere will cherish it dearly.

What is Trotskyism?

Political ideas – especially complex ones – often struggle to be defined coherently. Trotskyism is no exception. Kelly identifies nine ‘core elements’, though a number of these are actually beliefs held in common with Lenin and the Bolsheviks (Trotskyists see themselves as their true heirs) together with their advocates in the various ‘Communist’ parties and regimes across the world this last century or so.

One of the core elements is more fundamental than most of the others and – despite the excellence of the book in other respects – has not been brought out quite as clearly as it might have been. This is the idea that while the working class is considered to be the agent of social change – as in Marxist theory generally – it is deemed incapable of doing this while capitalist rule dominates. This was the view taken by Lenin and the Bolsheviks, including both Stalin and Trotsky, and so unites them all.

From this viewpoint much else follows. If the working class is unable to understand capitalist exploitation and overthrow the capitalist system because the dominant ideas are literally always those of the ruling class, then how can a socialist revolution ever occur? All those in the tradition of Lenin came up with an answer, based on adapting the Russian Bolshevik model of a minority political coup d’etat. This idea was to build up a political party of professional revolutionaries (the ‘vanguard’ or ‘advanced guard’ of the working class) that could overthrow the capitalist government. It could then try to create the economic and political conditions for a socialist society – including the desire of the working class for it – after the event. Rather like having the pregnancy after the birth.

But to build up the vanguard party of professional revolutionaries within capitalism there’s no point advocating socialism, as that would be to cast pearls before the proverbial swine. What is needed instead is a tactical approach that can form an ideological bridge between where we are today and where we could end up. And this, in most respects, is where Trotsky and his followers developed a set of theories – most of them really tactics – that have distinguished them from others in the tradition of Lenin and the Bolsheviks. In particular:

Transitional demands. These are reforms of capitalism advocated with the sole purpose of demonstrating that the system can’t deliver them. This creates tension with genuine reformists like those in the mainstream Labour and Social Democratic parties who know they are unattainable and unrealistic, so prefer not to pursue them. But for Trotskyists the point is to create disillusion with the system and its established leaders so that the more critical, questioning members of the working class will turn away from them and towards the leadership of the vanguard party instead.

The ‘united front’ tactic. Like advocating transitional demands, this has been a means of winning recruits from other parties as it involves putting forward specific demands and campaigns that will enable Labour, Communists, Trotskyists, etc to work together on certain issues such as anti-fascism, while enabling Trotskyists to remain critical of their partners in other respects. This is just slightly different from the old Communist Party tactic of the ‘Popular Front’ which had often involved overtly pro-capitalist parties too, like Liberals.

A critical stance towards the former Soviet Union and its satellites. This is the big issue that has created more disagreement in the Trotskyist movement than probably any other. This is because while all wish to be critical of the regime Stalin went on to build up while Trotsky was in exile, they nevertheless hold very dear to the political methods that created it in the first place. Trotsky’s own formula was to label Russia a workers’ state that had degenerated under Stalinist leadership. Some still adhere to this, while others have moved from this position over time to create greater distance, adopting the view that these countries became state capitalist, or were some other form of class society.

A ‘catastrophist’ interpretation of capitalism. Trotsky’s seminal text in 1938 was The Death Agony of Capitalism and the Tasks of the Fourth International and most Trotskyists believe capitalism has been in its death throes ever since, 80 years and counting. This view is not entirely exclusive to them, but they link it vigorously with the need for working class ‘leadership’ ie themselves as the vanguard party that can rescue the working class from crisis.

The need for a ‘Fourth International’ or similar. This is as a successor to the old Third International or ‘Comintern’ associated with Stalin and the Soviet regime. It would be an international body linking and uniting Trotskyist vanguard parties across the world with common perspectives, and also under a broadly common programme and set of tactical approaches.

The idea of spreading ‘permanent revolution’. This stands in distinction to the Stalinist idea that socialism could be built in one country and by stages, as Trotsky held the view that revolutions – if they were to succeed – needed to spread and not become isolated, hence the need for a Fourth International. Nevertheless, the idea of a socialist revolution being one where a minority vanguard party takes power and then nationalizes the economy (as in Soviet Russia and China) is the same as the conventional Leninist and Stalinist view.Trotskyism in Britain

One of the most notable features of the Trotskyist movement in Britain and other countries has been its tendency to fragment over time. From its origins in the tiny Balham Group of former Communist Party members in the 1930s it was united for a short time towards the end of the Second World War in an organization called the Revolutionary Communist Party, but since then has been split asunder many times.

Kelly has identified seven Trotskyist ‘families’ that emerged, though this is perhaps a little over-theorized. In reality, four main tendencies surfaced in Britain in the post-war era after the split of the RCP and these were led by four dominant individuals. This is perhaps not surprising. Trotsky himself had claimed that ‘The world political situation as a whole is chiefly characterized by a historical crisis of the leadership of the proletariat’ and Trotskyist organizations (like Lenin’s Bolsheviks) are characterized by top-down structures based on the principles of what they call ‘democratic centralism’, effectively designed to ensure self-perpetuating leaderships.

The four main Trotskyist organizations that emerged in Britain from the 1950s and 60s onwards may be familiar:

The Workers Revolutionary Party (WRP), formerly the Socialist Labour League, which was founded and led by Gerry Healy until it split into myriad fragments in the mid-late 1980s. This tendency has been characterized by Kelly as Orthodox Trotskyism, and it is hard to disagree as it holds rigidly to what it sees as Trotsky’s perspectives and recommendations before his death and has been known for its extreme sectarianism and hostility to other organizations.

The Militant Tendency (really called the Revolutionary Socialist League), led by Ted Grant and which became the most well-known Trotskyist organisation through its control of Liverpool City Council in the mid 1980s and its ‘deep entryism’ inside the Labour Party, even at one stage having three Labour MPs. It split in the early 90s and its successor organizations are the Socialist Party of England and Wales (SPEW) and Socialist Appeal. Kelly calls this tendency ‘Institutional Trotskyism’ because of its adherence to supporting Labour and use of parliament, though most of its attitudes, perspectives and ingrained sectarianism are not dissimilar to the Orthodox Trotskyism of the WRP – the main difference being that the WRP/SLL in its early life used entryism into the Labour Party as a tactic (as did the other main Trotskyist tendencies) whereas Militant made it a point of principle.

The International Marxist Group (IMG) led by Tariq Ali. This became the British section of the United Secretariat of the Fourth International (for a while the dominant semi-official one), hence Kelly’s description of this as Mainstream Trotskyism. This is perhaps a little confusing as it was mainly noted for attempts by its international leaders Ernest Mandel and Michel Pablo to revise and update Trotsky’s ideas in an era of Third World revolts and student agitation. Again it splintered into various competing sects, some inside the Labour Party and some outside it, the most well-known survivor probably being Socialist Resistance.

The Socialist Workers Party (SWP), formerly International Socialism and led until his death by Tony Cliff. This is currently the largest of them all, even though it has suffered more splits and splinters than most, including in recent years. It was originally influenced as much by the ideas of Rosa Luxemburg as by Lenin and Trotsky and its distinguishing feature is its view that the Soviet Union and its satellites became state capitalist when Stalinism took hold, adopting a standpoint previously alien to the Trotskyist movement and pioneered by non-Leninist organizations like the SPGB. Kelly categorizes the SWP and most of its offshoots as ‘Third Camp’ Trotskyism.Upwaves and downwaves

Kelly argues with some evidence that there have so far been four distinct phases in the British Trotskyist movement: 1950-65 which were the ‘Bleak Years’ of limited growth while inside the Labour Party, the ‘Golden Age’ of membership growth and influence from the mid 60s to mid 80s while the traditional Communist Party declined, then a period of ‘Fracture and Decline’ from the mid 80s until around 2005, when a period of ‘Stasis’ has endured.

There are currently 22 separate Trotskyist organizations in the UK though their total membership is less than 10,000 – well under half of the combined peak membership of the mid 1980s. Some organizations have splintered off over time and have moved away from Trotskyism such as the Revolutionary Communist Group (RCG), though these, along with Stalinist and Maoist-type groups, also have memberships that tend to be numbered in the low hundreds at best and more typically much less than that.

The commitment expected of members of Leninist organizations generally can be considerable, with many Trotskyist groups mapping out their members’ free time in any given week and expecting significant financial contributions – the Alliance for Workers Liberty (AWL) had average annual membership contributions per head of over £330 a year in 2014 and Workers Power has effectively charged a ‘tithe’ of 10 per cent of income. This is in large part what enables Trotskyist groups to publish a very regular press and many even now are built around the sales of their newspapers and magazines. The WRP famously received funds from Libya and other Middle East states but this is exceptional – most Trotskyist organizations lurch from internal financial crisis to crisis, being repeatedly bailed out by their membership to keep their loss-making publications going. Nevertheless, the Revolutionary Communist Party of the 80s and 90s (a grandchild of the IS/SWP) and publisher of Living Marxism was bankrupted by a £1 million libel action from ITN. Today only two papers have regular print runs (not sales) of over 2,000, these being Socialist Worker (SWP) and The Socialist (SPEW), with print runs of 20,000 and 10,000 copies respectively per week. Some organizations are so small they only produce irregular magazines or concentrate on maintaining a web presence.

Staffers

One of the more intriguing details to emerge in Kelly’s book is how much activity is stimulated and supported by paid officials. During the Militant Tendency’s peak of 8,000 members it had no less than 250 full-time equivalent staff (a not dissimilar total to the entire Labour Party). More recently, SPEW has the highest number of staffers with 45 full-time equivalent workers, compared to 32.5 in the SWP. Most of these are employed in publications-related work, with some being national, regional or campaign organizers.

Given all this, and the campaigns both initiated and hijacked by Trotskyist groups (from the Anti-Nazi League in the late 70s to the Stop the War Coalition more recently), it is perhaps surprising they remain as small as they do. Even more surprising perhaps given their relentless work in the trade unions, including trying to gain positions of influence at all levels, again meticulously detailed by Kelly. Similarly, in the last couple of decades there has been a generally increased focus on election campaigns as a means of generating publicity, from Respect to the Trade Union and Socialist Coalition (TUSC). This has led to some long-term sworn enemies like the SWP and SPEW temporarily bury their differences, but with little practical effect.

Prognosis

The current state of flux in the Corbyn-led Labour Party has seen a number of Trotskyist groups identify a chance to engage closely with people who could be like-minded. The paucity of Trotskyist candidates standing against Labour in the 2017 General Election was a reflection of this, reversing the trend towards greater electoral participation since the 1990s. The evidence presented by Kelly suggests that the far left tends to do better on average (both in terms of electoral support and in party membership) when Labour is in government rather than in opposition. But it still does badly, and even organizations in other countries including some Trotskyist elements within them at various stages such as Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain only succeed when they build far wider leftist coalitions, dwarfing the Trotskyist contribution to the extent that it becomes almost invisible. And almost inevitably these parties have a tendency to end up – like Syriza – being respectable parties of capitalist government.

This is interesting, because Trotskyist groups have long argued that they do this because to do anything differently, such as advocate real socialism (common ownership, production for use, the abolition of the wages system, etc) is a waste of time. In fact, most of them only pay lip-service to this as being their long term goal at very best, and most take the traditional view of the Communists (ie Stalinists and Maoists) that socialism is really a nationalized, planned economy under the control of the vanguard party. But as in Soviet Russia this leaves all the economic features of capitalism intact – such as wage labour, production for sale on markets, etc – and is really just state-run capitalism.

It all gets to the essence though of why socialists oppose the Trotskyist movement and have long warned of the dangers of being involved in it:

- they do not advocate (or in many case really believe in) socialism but actually believe in a form of state run-capitalism under their own leadership

- they are elitist organizations that are dominated by small and generally unaccountable groups of leaders who see themselves as potentially great historical figures, guiding the masses with their supposedly superior political tactics

- they are politically dishonest as they advocate demands (the ‘transitional programme’) in the full knowledge they cannot be met within capitalism and will only create disillusion – indeed that is the entire point of advocating them

- they will periodically enter and otherwise give support (however ‘critical’) to anti-socialist organizations like the Labour Party

- they have a well-known history of hijacking trade union and other struggles for their own ends.Of course, we are well aware that they don’t have a high opinion of us either. We are usually guilty of things like ‘abstract propagandism’, which means not arguing for reforms of capitalism and they have sometimes derided us as the ‘Small Party of Good Boys’ and similar.

While we are far smaller than we would like to be and can certainly learn lessons from the last century and more, John Kelly’s book has thrown an interesting spotlight on a few things. And one of them is that despite the fact that we in the SPGB advocate the ‘maximum programme’ of socialism and nothing but – and despite all the tactical manoeuvrings and reform campaigns of the various Trotskyist groups over the years – there are only two of them (the SWP and SPEW) that are actually bigger than us! Every other party and group from the WRP and Socialist Appeal to the AWL and Counterfire are smaller than we are. And so were former (and very visible) Trot groups like the RCP at their peak in the late 80s/early 90s.

Just think, then – if a few more of them had spent their considerable energies advocating real socialism rather than playing tactical games of footsie with the reformists, the movement for social change in this country would be a lot stronger than it is. That’s not to crow, as we of course wish we were a lot bigger than we are – but just to point out that the tactical genius of Leon Trotsky and his latter-day followers has been rather misdirected and somewhat over-rated. And that’s us trying to be polite.

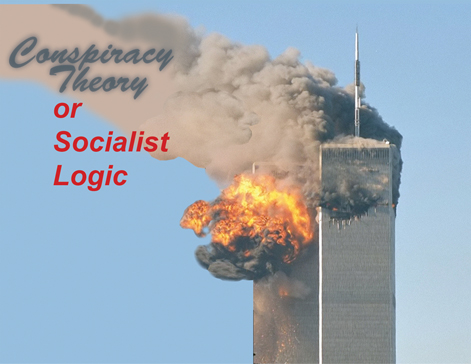

Conspiracy-theory, or conspiracism, has it that much of the world today is to be understood in terms of ‘conspiracy’ be it by scientists, extra-terrestrials, masons, or whoever.

Currently gaining credence among many is the idea that all accepted science is a conspiracy, for relativity theory and quantum physics are specialised subjects. Einstein is difficult to understand and the majority of us are not astrophysicists, or other types of scientist, but that is no reason to dismiss these theories.

Many in society seek solace in pseudoscience, and therefore in conspiracism, whereby they can feel in control over what they cannot understand. Conspiracism absolves you from having to undertake painstaking research where you are not willing to trust those who actually have expertise in a difficult subject. Conspiracism attracts people from an entire spectrum, eager to feel that they belong to something: right or left in their leanings, dependent on what they were before becoming conspiracist. The phenomenon appears to attract ‘truthers’ – those who know the ‘truth’ despite the facts. Some are avowedly Christian, others not. Some dally with other rehashed mythologies, interpreted to fit in with their modern conspiracism. Many are, in fact, as members of the working class, confused and vulnerable, and want to feel significant; which they feel modern scientific thinking cannot help them with.It is tempting to draw some similarity in all of this to the declining years of the Roman Empire, so brilliantly shown in the film Agora, about the last days of the great Library of Alexandria. Science and learning were then the property of a privileged few, and this is largely how they are seen today by many attracted to conspiracism and ‘truthism’. Today we are bombarded, flooded, with ideas and theories via the internet, whilst actual reading has declined. Some conspiracy theorists tend to deride books which contradict them, dismissing them as the propaganda of those ‘in on’ the ‘great conspiracy.’ Book-learning becomes associated with closeted academia and so is deemed irrelevant. So refutation of a conspiracist's ideology from facts outlined in books is futile.

With many people feeling disenfranchised from intellectual life, as they are in fact disenfranchised economically (being born in the wage-slave class), old and new-style forms of fanaticism win converts. Conspiracism is an obstacle to socialist awareness. Vital to the spread of socialist awareness is the materialist conception of history and recognition of human scientific progress.

Marx knew this when he wrote welcoming and applauding the publication of Darwin's The Origin of Species, recognising science as the necessary ally of socialism. Above all, the scientific study of history is vital and paramount, as history is an evolutionary process.

Capitalism is not a conspiracy. It is a system that evolved through social and economic processes, just as socialism will have done. Capitalism, and class societies as a whole, do by definition encourage ‘conspiratorial’ behaviour, but they are historically, not ‘conspiratorially’, produced.

Everything grows from an antecedent and does not appear out of the blue.Conspiracy theory backs up the bourgeois myth of an evil human nature (‘Original Sin’ rehashed for the modern age). To paraphrase Karl Marx, the morality of a given age is the morality of its ruling class. The cut-throat values of the capitalist class have us believing in a human cut-throat nature in which everyone is a potential conspirator, a potential thief, a potential brigand. Thus an ideology of brigandage, sustained by the viciously competitive nature of capitalism, leads people to see their fellow beings as either real or potential brigands.

Conspiracism reduces everything to a school playground view wherein everything is viewed as the

machinations of some cartoon-like gang independent of history. Those who attempt to spread conspiracy theory do a disservice to the cause of achieving a better world, by further confusing already confused workers and by giving ammunition to those who label socialists as cranks and claim capitalism to be the end of history.We urge our fellow workers to face reality, embrace knowledge, and recognise for what it is the ridiculous zealotry known as conspiracy theory. Emancipation from the system of wage-slavery, poverty, prices and profits requires a grasp of social history and of social and natural realities.

Whale Flukes

When people ask questions that begin ‘What would socialism do about…?’ we have to be careful how to answer because a) it would be presumptuous of us to make tomorrow’s decisions today on behalf of everyone, b) prevailing circumstances and technology may change unpredictably and c), as a Party wag once put it, socialists don’t have crystal balls.

But you don’t need technical knowledge, or crystal balls, to realise what socialism would most likely do in many cases. Sometimes common sense is enough. But capitalism is far too perverse to be so amenable, as two recent news items illustrate.

The first item is the story that Japan is trying to get its supporters on the International Whaling Commission (mostly small countries with juicy Japanese aid programmes) to vote to lift the long-standing global embargo (‘Japan says it's time to allow sustainable whaling’, BBC Online, 7 September). The whaling question is bizarre from almost every angle. Japan argues that now that the minke whale population has returned to sustainable levels, the embargo makes no sense. But Japan has famously been hunting minke whales in defiance of the embargo ever since it was established in 1986, with the risible pretence of ‘scientific research’. This oddity seems to be what has drawn so much media attention onto Japan, while to virtual media indifference and without any such ‘scientific’ pretence, Norway and Iceland together hunt even more whales per year than Japan, including the endangered fin whale. Their reason? The IWC embargo was only ever voluntary and so they have both opted to ignore it. One wonders why the Japanese don’t simply do the same.

After all, they would have a point. The IWC was deliberately crowded out by non-whaling countries (over 70) to permanently out-vote the whalers, so the debate was harpooned from the start. The Japanese are also surely correct in pointing out that most opposing countries support large-scale meat farming, often in cramped and inhumane conditions, and are thus being completely hypocritical. Certainly whales are intelligent animals, but then so are pigs. Moreover it’s a strange kind of moral argument to say that we shouldn’t kill things because they are intelligent, when capitalism regularly kills intelligent humans by the tens of millions, by neglect if not active warfare.

But what’s really odd about the whaling industry is that it doesn’t even make money. Whaling in all three countries is heavily subsidised by their governments. Though populations have been gulled into supporting whaling as a mark of nationalist pride, hardly any of them eat whale meat. In Iceland, whale watching is a far more lucrative industry and almost the only people who eat the meat are tourists who think of it as a cultural box to tick (‘Icelanders Don’t Like Whale Meat—So Why the Hunts?’news.nationalgeographic.com, 27 January 2016).

In Norway fewer than 5 percent eat whale steak (Wikipedia). The rest is sold for dog food or shipped to Japan. Even in Japan there is hardly any taste for it, and the market is on the point of collapse. The reason in all cases is the same: whale meat just doesn’t taste very good. Despite its claims to centuries of tradition, Japan only started large-scale whaling after World War 2 when it was unable to afford lamb and beef imports.

Norway’s only remaining whaling company actively propagandises the industry by visiting schools and sponsoring apprenticeship schemes. Iceland echoes a Life of Brian parody by demanding the right to eat whale as a symbol of national independence even though none of them do, while Japanese ‘scientific’ whale meat usually ends up in restaurants served to tourists. Meanwhile government subsidies keep the leaky ship afloat. The more you look at the industry, the madder it gets, and it serves as an example to anyone tempted to argue that capitalism’s market system is always supremely logical and economically rational. It sometimes isn’t, even in its own terms.

To answer the question ‘Would there be whaling in socialism?’ you only have to ask yourself if you would be prepared to go out on a factory ship and kill whales with grenade harpoons for the sake of something that nobody wants to eat in the first place.

The Green And Pleasant Sahara

The other story is more encouraging, with the suggestion by researchers that planting up to 9m square kilometres of solar panels and wind turbines across the Sahara desert would have the effect of greening it (‘Large-scale wind and solar power 'could green the Sahara'’, BBC Online, 7 September). It turns out that both solar and wind collection systems have the by-product of increasing local precipitation, quite apart from the energy they produce. The effect on local people could hardly be more positive, in turning arid desert into a Garden of Eden, so unless further climate modelling produces the unhappy report that more rain on terrain A means less rain on terrain B and that such a project would wreck the global climate even more than it’s currently being wrecked, there appears to be no down side. It’s estimated that such a project could generate up to four times the entire world’s annual energy consumption. In a socialist society looking for safe and sustainable ways to produce abundant energy, this could well be the decisive factor in proceeding with such a scheme in all haste.

But in capitalism there is the unpredictable market to take into account. What rich country or corporation is going to front up the money for this, and toward what perceived profit? Local people in the Sahara may well benefit but as they are among the poorest people on Earth they don’t count, economically speaking. What does count is the sale of the energy to other countries, but energy prices can be severely affected by many factors, especially oversupply. Investors are not likely to invest in any system that supplies energy over and above projected demand, because this will lead to lower prices and a loss of profit. So, good as the idea looks, if the numbers don’t add up capitalism won’t build it.

Or maybe they will, if they apply the farcical logic of the whaling industry. No wonder socialists think capitalism is bonkers.

In our August issue we challenged those leftists who still cling to the belief that the Sandinistas in Nicaragua represent a progressive ideology. Many of those same left-wingers also continue to support and sympathise with the Maduro government in Venezuela and are excusing the authoritarian excesses that are taking place. They are reluctant to forget Hugo Chavez, and how he invested part of Venezuela’s oil wealth into social benefits for poor people that resulted in his popularity.So, to explain the failure of his successors to continue this, they place blame for the current collapse of civil society elsewhere. American imperialist interference is said to be the culprit for the destabilisation of the Venezuela government by conspiring with the right-wing to overthrow Maduro by creating conditions for the breakdown of the economy. The USA has indeed imposed sanctions on Venezuela with this aim, and many Venezuelan businesses did divert their stocks to more profitable markets leaving shop shelves empty. But there is more to it than that. Chavez's social policy was based on the rents from oil production remaining high. When oil prices fell, this could not continue and recourse to the printing press and price controls has resulted in shortages, inflation and unemployment, causing discontent.Venezuela's economic crisis and virtual collapse began a few years ago when rapidly falling oil prices meant that Chavez's policy of subsidising the poor could not continue. The attempt to do so has transformed Venezuela into a humanitarian catastrophe which has turned the world's media spotlight on the economic chaos and the dire conditions of the people there.It has been reported that because of the high prices and shortages of food, in 2017 Venezuelans lost on average 11 kilograms (24 lbs) in body weight last year, nicknamed the 'Maduro Diet'. UN Commission for Human Rights spokesperson Ravina Shamdasani says that 87 percent of the population is now affected by poverty:'The human rights situation of the people of Venezuela is dismal. When a box of blood pressure pills costs more than the monthly minimum salary and baby milk formula costs more than two months’ wages – but protesting against such an impossible situation can land you in jail – the extreme injustice of it all is stark'.Unemployment has reached 30 percent. The IMF predicts that Venezuela's inflation rate may well hit one million percent by the end of 2018. The situation has grown into a refugee crisis for Venezuela's neighbours.The UN has said that more than 7 percent – 2.3 million – of Venezuela’s population has left the country since 2015 to escape political violence and severe shortages of food and medicines. More than a million of them have crossed into Colombia since 2015. About half a million Venezuelan citizens have entered Ecuador since January. That is nearly 10 times the number of migrants and refugees who attempted to cross the Mediterranean into Europe over the same period. Ecuador has declared a state of emergency in its northern provinces. This year 117,000 have claimed political asylum in Brazil. Up to 45,000 Venezuelans have crossed the narrow straits to Trinidad and Tobago. Many other countries have imposed strict entry restrictions.

According to UN Refugee Agency spokesperson William Spindler:

'The exodus of Venezuelans from the country is one of Latin America's largest mass-population movements in history. Many of the Venezuelans are moving on foot, in an odyssey of days and even weeks in precarious conditions. Many run out of resources to continue their journey, and left destitute are forced to live rough in public parks and resort to begging and other negative coping mechanism in order to meet their daily needs'. He added that 'xenophobic reactions to the exodus have been noted in some quarters.'Venezuelan Vice-President Delcy Rodríguez said the figures had been inflated by 'enemy countries' trying to justify a military intervention. Maduro has put the number at 'no more than 600,000 in the last two years.'

Capitalism cannot be made to work in the permanent interest of the workers, even though there can be some temporary respite with pro-worker reforms. When the price of oil fell these temporary benefits in Venezuela could not be sustained. In the end, the economic laws of capitalism asserted themselves. The problem is that left-wingers never learn from history. They discover what they believe are shortcuts to socialism but which ultimately lead to disillusionment. It is the same mistake they repeat over and over again, resulting in our fellow-workers swinging back and forth like a pendulum from left-to-right and right-to-left.What is most disappointing for socialists, aside from the despair and misery of our fellow-workers, are the left wingers who argued that Venezuelan Chavismo was somehow the path to 'socialism' (actually state capitalism, relying on oil rents). Such claims merely offer ammunition for the pro-capitalist apologists to say 'Look at what's happening in Venezuela – that is socialism for you'. But it wasn't.

Politics

A month or so on from the horrific floods and consequent devastation in the state of Kerala, south western India, it is interesting to look back at the commentary being put out by Indian writers at the time. There is blaming and shaming of different varieties, of different parties, with different emphasis depending on the main points raised by each individual commentator. This particular incident though, however serious and shocking, cannot be isolated from the many other such weather catastrophes occurring globally with greater frequency. One has to wonder just how seriously unaffected individuals view such disasters and how long the incidents remain in their minds. Are such disasters even perceived as something that any individual can do anything to change? Political commentary in one country relating to events in that country can have only limited effects. When talking of climate catastrophe the political discourse must be global. The necessary action must be global. All events need to be seen, not separately, but as parts of the whole.Differences in emphasis between the government of the State of India supporters, (the nationalist BJP,) and those of Kerala State government supporters, (so-called Communist ie allegedly ‘Marxist’) was, as to be expected, widely different and the blame game could be clearly seen as political. For instance the local state government called very early on to the central government for assistance with troops, equipment, vehicles, helicopters, etc., but were dismissed for ten days before the floods were recognised nationally as 'a severe calamity', at which time limited help was given, gaining praise from BJP supporters and derision from local government backers. Central government also refused offers of assistance and donations from outside the country whilst within Kerala State itself local organisations quickly rallied thousands of volunteers from among their ranks of students, youth, trade unions, etc., both members and supporters, with volunteers in control rooms at fourteen district administration headquarters, while12 thousands of fishermen with more than 600 boats evacuated the bulk of those rescued. It should be noted that the BJP has scant political representation in the whole of south India, so stands on the sidelines in Kerala.

South India has approximately 20 percent of India's population and contributes about 30 percent of total taxes. Its share in total GDP is 25 percent but receives only 18 percent in return. Kerala State, a part of S India, is recognised by international organisations as having the best human development indicators in India.

Monsoon, Water, Statistics

In recent years the monsoon season has become more and more unpredictable resulting in years of drought and crop failure followed by sudden inundation causing loss of top soil and consequent problems. This most recent flood happened during the expected monsoon season but was much greater than the previous 'biggie' a century earlier. Hundreds of thousands of people were evacuated safely from below many of the dams in the few days before the flood happened.According to the publication Nature, 'there has been a 3-fold increase in widespread extreme rain events over central India during 1950-2015, increasing the events of flooding which is linked to rapid surface warming on the northern Arabian Sea which borders Pakistan and NW India.' The former advisor and founder of the Climate Change Research International says that expected increases in extreme weather events due to climate change reveal India to be more vulnerable (than many other countries) because of its wide geographical and demographic variations.

Expert after expert confirms on a regular basis that what is happening globally, that is increasing extreme weather events, is not a surprise but just what was expected and warned about.

In 2016 Kerala suffered its worst drought in 115 years requiring severe water rationing. This was soon followed in 2017 by 440 wild fires that destroyed 2,100 hectares of forest. Then came the 2018 flooding when 80 dams in the state had to be opened (of which 42 are major dams) causing 44 rivers to overflow. Kerala's annual average rainfall, the highest among all 'big' Indian states, is close to 3,000mm – more than double that of the UK, and most of it will fall during the three months of the monsoon season. This year, from June 1 to August 21, 41 percent more than normal rain fell, and in the latter 19 days, 164 percent more than normal, causing massive flooding and landslips affecting all districts of the state. Including the huge numbers of evacuees, current figures state that some 5.4 million people have been directly affected.

India's population is 15 percent of the global total with just 4 percent of global water resources.

65 percent of farm land depends entirely on rain. A comparison is revealing:• There are 4,525 dams, large and small.

• Per capita water storage: 213 cubic metres.

• Per capita water storage Russia: 6,103 cubic metres.

• Australia: 4,733 cubic metres.

• US: 1,964 cubic metres.

• China: 1,111 cubic metres.Regarding the water table, information taken from a European Commission report reveals that currently there are more than 20 million boreholes, up from tens of thousands in the 1960s. The water table is falling on average by 0.3m – 4m annually meaning that wells dug in the '60s to a depth of 15m are now having to go to a depth of 91m to find water. In some areas wells at depths of 500m have gone dry.

It's All About Politics

To return to the political agenda, and being aware of the dire water situation, currently the national government is now encouraging the growing of sugar cane, rice and other 'water heavy' crops in areas of traditionally low rainfall, dancing to the tune of multinational corporations eager to gain access to more farmland. In 40 years Kerala has lost nearly half its natural forest, some to monocrops and some as urban areas continue to expand. Both of these factors cause problems for sudden flows of water, less being absorbed naturally and thus causing rivers to overflow. 'How quickly rivers change and how quickly we respond with urban drainage and flood mitigation measures will play a significant role in our evolving flood risk. Further to this will be how rapidly societies and their governments begin to adopt more resilient ways of living with water.' (http://theconversation.com/kerala-shows-the-risk-of-severe-floods-is-still-evolving-101880).The biggest handicap to implementing any of the above measures is the current global political system's lack of interest.

Take for instance the current tense situation between the neighbouring states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu. The struggle is between dam safety (Kerala) and water availability (Tamil Nadu). This one particular dam and all its catchment area is in Kerala but operated by Tamil Nadu through a very interesting colonial history. The dam, 123 years old, diverts some of the water east into Tamil Nadu's Vaigai river – dating from an 1886 agreement between the British Madras Presidency and the Kingdom of Travancore. Why is this relevant now? Because the case had to be referred to the Supreme Court for judgement to have the level reduced 3 feet against Tamil Nadu's wishes.

As of 2 September 483 deaths have been recorded as a result of this latest flooding in Kerala; more than 1.5 million people are in relief camps; thousands of homes have been either inundated or swept away and roads and a major airport have been seriously damaged. According to ecologist Dr S. Faizi:

'This was a man-made calamity predicted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2007.' The calamity was fewer rainy days but a greater volume of precipitation. The IPCC prediction was that 100-year flood cycles will change to 4-5 year cycles - and soon. The victims of this particular climate catastrophe are amongst the smallest emitters of greenhouse gases globally.According to a 2013 World Bank Study: US per capita emissions: 16.4 metric tonnes. India per capita emissions: 1.6 metric tonnes.

Kerala in context: just one small snapshot from a huge collection of global disaster scenarios caused by a world political system forging ahead to achieve its main objective - profit - whatever the consequences.

The Reformism of the Hard Left

The social revolution to replace minority class monopoly over the means of production by common ownership finds a formidable barrier in the guise of reformism to which the Hard Left, every bit as much as any mainstream capitalist political party, is fundamentally wedded. It is important to precisely define what we mean by this term. It is very easy to conflate reformism with other forms of activity, notably trade unionism, on the grounds that both seem to have in common the aim of improving the welfare and wellbeing of workers.However, it would be a gross error to see trade unionism as a type of reformism. In the Introduction to her pamphlet Reform or Revolution (1900) Rosa Luxemburg, for one, seemed to commit this very error:

‘Can the Social-Democracy be against reforms? Can we contrapose the social revolution, the transformation of the existing order, our final goal, to social reforms? Certainly not. The daily struggle for reforms, for the amelioration of the condition of the workers within the framework of the existing social order, and for democratic institutions, offers to the Social-Democracy an indissoluble tie. The struggle for reforms is its means; the social revolution, its aim’.

What underlies this thinking is the understandable fear that the revolutionary goal might seem somehow divorced from the ‘daily struggles of workers’ if it did not appear to endorse the latter. But this fear is misplaced for reasons that have already been touched upon

Reformism is distinguishable from trade unionism by virtue of the fact that it is essentially political in nature. That is to say, its field of operation – like revolution itself – is political whereas the field of trade union struggle is bargaining with employers.Reformism entails the state enacting various legislative measures that are ostensibly designed to ameliorate certain socio-economic problems arising from the capitalist basis of contemporary society – without, of course, posing any kind of existential threat to the continuance of capitalism itself. In other words, reformism seeks to mend capitalism. As such it runs completely counter to the socialist goal of ending capitalism.

The futility of reformism was no better summed up than by the revolutionary socialist, William Morris, more than a century ago in How We Live and How We Might Live (1887):

‘The palliatives over which many worthy people are busying themselves now are useless because they are but unorganised partial revolts against a vast, wide-spreading, grasping organisation which will, with the unconscious instinct of a plant, meet every attempt at bettering the conditions of the people with an attack on a fresh side’.

Capitalism by its very nature has to operate in the interests of capital, which interests are fundamentally opposed to those of workers. The accumulation of capital, whether in the hands of private corporations or the state, expresses itself in the remorseless drive to maximise the amount of surplus value – ‘profit’ - extracted out of the labour of working people and is, thus, firmly predicated on the exploitation of the latter. This is not a matter of choice but of economic necessity. It is the very condition of commercial survival - not to mention, expansion - in a world of ruthless economic competition. Quite simply, any business that did not make a profit out of its workforce would soon go out of business.

Were the Hard Left ever to secure political power it would soon enough find itself politically imprisoned within the constraints imposed by the non-socialist outlook of the majority and thus forced to continue with the administration of capitalism in some form. This follows logically from the very premise of its own vanguardist theory of revolution. Vanguardism is defined as the capture of political power by a small minority ostensibly acting on behalf of the working class majority in advance of the latter having become socialists. Since socialism cannot come about without the latter becoming socialists this means that, for the time being, a Hard Left government would have no option but to continue by default with the administration of capitalism.

The Hard Left may protest that this is to overlook the whole point of a socialist minority capturing power before a majority had become socialist – namely, to be in a position to be able then to counter the enormous weight of capitalist propaganda in order to infuse workers with a socialist consciousness. How can you do that without this minority first capturing the state?

Actually, this is yet another example of the Hard Left shooting itself in the foot. While it is all too ready to scornfully characterise the so-called ‘abstract propagandism’ of the Socialist Party as ‘idealist’, arguing that ‘practical experience’ is the way we become socialists rather than through the dissemination of socialist ideas – as if these two things can ever really be separated – it conspicuously chooses not to apply this very same argument to itself and in its own theory of vanguardism.

What, for instance, does it imagine would be the result of the ‘practical experience’ of a Hard Left government having to administer capitalism? Since capitalism can only really be administered in the interests of capital, and not wage labour, such a government, like any other capitalist government, would be compelled to come out and oppose the interests of the very workers it claimed to represent. In other words it would be compelled to abandon any thought of inculcating socialist consciousness into workers since to do that would defeat or, at least, seriously impede, the very purpose to which it had resigned itself – namely, the effective administration of capitalism. You can’t effectively administer capitalism with millions of people beginning to question, and oppose, the very basis of capitalist society – class ownership of the means of wealth production.

The Hard Left, while fond of rebuking others for their philosophical ‘idealism’ shows its own attachment to ‘idealism’, in its utterly lame attempts to explain away the all too obvious shortcomings of the so called “proletarian states” to which it has historically pledged allegiance - from the establishment of the Soviet Union onwards. Even today Leftist supporters of such transparently obnoxious anti-working class regimes as Maduro’s Venezuela or Kim Yong Un’s quasi-monarchical North Korea will perform political gymnastics to justify this craven, not to say cringing, support. Their gullibility seems to know no bounds.

For the regimes in question a few petty, token pro-worker reforms or the ritual bombastic denunciation of that ogre of ‘American imperialism’ (as if imperialism is limited to just the US and its European allies) will suffice to have the Hard Left meekly eating out of their hands and sycophantically trying to rationalise every twist and turn of policy designed to tighten the screws on the workers in these countries.

When evidence of the anti-working class nature of these regimes becomes too overwhelming to ignore, the excuses offered will be couched in terms that do not – and dare not - question the basic tenets of vanguardism itself. The failure of the ‘proletarian state’ to make good its promises to the workers will be attributed to the various character flaws and the betrayal of the Leadership in its ‘drift to the Right’. If only Trotsky had got into power and not Stalin, exclaims our fervent Trotskyist, then things would have been so different and so much better. The irony of rebuking socialists for being ‘idealists’ while endorsing this idealist ‘Great Man’ theory of history could hardly be richer.

Reforms and ReformismPart of the reason why the Socialist Party comes in for so much criticism for its opposition to reformism is that it seems to suggest an attitude of callous indifference to the plight of fellow workers. Is it not clearly the case that certain reforms can be beneficial to the working class or at any rate, certain groups of workers?

Well, yes, of course some reforms can be of some benefit to workers. This is not denied. Socialists are not opposed to particular reforms as such but, rather, to reformism – that is, to the practice of advocating or campaigning for reforms. Once you go down that road there is technically no limit to the number of reforms you might then want to push for. Sooner or later in your bid to push for reforms, the revolutionary objective of fundamentally changing society will be overwhelmed, side-lined and eventually forgotten altogether. The entire history of the Second International, and of the Social Democratic and Labour parties of which it was composed, unequivocally shows this to be the case.

Not only that, any benefits that particular reforms might provide are likely to be transient and provisional and dependent on the current state of the market itself which is always subject to fluctuation. Reforms that can be given with one hand can also in effect be taken away with other - that is, withdrawn in the interests of 'belt tightening' or simply honoured in the breach, particularly in the context of economic recession

Furthermore, insofar as some reforms provide some benefit to some workers they can sometimes be at the expense of other workers. Also, it is not only some workers that might benefit but some, if not all, capitalists too. It is, after all, mainly through the taxes paid by the latter to the state that reforms are financed. Increased taxation can undermine the competiveness of the businesses concerned unless the advantages accruing to them from the resultant increase in state spending outweigh the costs. This places a structural limit on what reformism can hope to achieve. Tax the capitalists too heavily and you kill the goose that lays the golden eggs that provides the state with its revenue.

In short, then, opposition to reforms as reforms is not at all the position of the Socialist Party though, surprisingly enough, such opposition is something that has, in the past, attracted support in certain quarters. In his book, Socialism (1970), Michael Harrington cited the curious case, in the late 19th century/early 20th century, of the American Federation of Labour, at that time led by the colourful figure of Samuel Gompers.

Gompers espoused a ‘voluntarist’ philosophy and ‘was hostile to all social legislation on the part of the government’. This stemmed from a quasi-Marxian conviction that the state inevitably governed in the interests of the ruling capitalist class and, consequently, any legislation emanating from it was bound to have the interests of that class in mind and thus be injurious to the interests of workers concerned. For that reason the AFL went out of its way to campaign against health and unemployment insurance, old age pensions and even helped to defeat referenda in favour of the eight-hour day.

Now this was obviously a ludicrous position to take but it also provides a salutatory warning of the dangers of blurring the distinction between economic and political struggles. As far as political struggle is concerned, the position of the Socialist Party is quite simply that it opposes reformism, not reforms, on the grounds that this is incompatible with the goal of achieving a socialist revolution.

Transitional demands

While the Hard Left goes through the motions of paying lip service to that revolutionary goal it is, nevertheless, fully committed to the struggle to reform capitalism. One of the ways in which it strives to rationalise this basically incoherent strategy in doctrinal terms, and thereby appear to give some credence to its revolutionary pretensions is by advancing the Trotskyist concept of ‘transitional demands’.

By this is meant a set of reforms that are supposed to differ in kind from the sort of reforms that, for instance typified, the so called ‘minimum programme’ espoused by the Second International. They are deliberately advocated by the Hard Left, on top of the minimum programme, in the full knowledge that they are unrealisable within capitalism. So, for instance, instead of pushing for a minimum wage of ten dollars an hour, you double, treble or even quadruple that figure. Yet even though such demands are unrealisable (since their implementation would spell commercial bankruptcy for the businesses involved which would, in turn, rebound against the workers employed in these businesses), they are still advocated. Why?

According to this crackpot theory what these so called transitional demands are supposed to do is to whet the appetite of workers for more ambitious change and so ultimately pave the way for the socialist transformation of society itself. In other words, they are supposed to bridge the gap between reform and revolution. Strangely enough, campaigning for the socialist transformation of society is considered ‘utopian’ by these theorists yet campaigning for a hopelessly unrealistic and unrealisable reform is not.

What this illustrates is the fundamentally manipulative and elitist outlook of the Hard Left. You cannot cynically engineer a socialist transformation of society behind the backs of the workers themselves. Apart from anything else that will more than likely backfire against you.

Workers are a lot savvier about the workings of capitalism than the Leninist vanguard seems to give credit. They are quite capable of sniffing out an opportunist politician offering pie in the sky when they meet one and the Hard Left, seemingly, will not be outdone in the size of the pie they offer.

Taboos and Criminality

Recently I was very surprised to discover that someone I knew and liked had, at one time, been convicted of sexual offences against under-aged females. He had been imprisoned for several years and was now hounded out of his job by an internet campaign. Many questions arise from this unfortunate situation including: (a) Can some crimes never be forgiven? (b) Does a completed prison sentence represent a relevant payment to the community? (c) Does the community (primarily parents) have the right to know of the presence of a convicted sex offender in their midst? (d) What is the relationship between social taboos and criminality?

Upon reflection I could find no examples of a universal cultural taboo. Murder, cannibalism, incest, paedophilia, abortion and prostitution have all existed (and if not sanctioned by authorities at least tolerated by them) in many cultures throughout history. The fact that these activities are taboos within certain cultures at certain times indicates an expression of identity (religious or humanist) that has been derived originally from a perceived communal necessity. For instance the Jewish prohibition against eating pork may originate in the unsuitability of the pig to thrive in an arid climate without access to vast uneconomical amounts of water or that the prohibition against incest has its origin in the need for human groups to forge alliances with others to improve their own survival.

A culture can identify itself as progressive through both criminalising taboos (the abuse of women and children etc.) and decriminalising them (homosexuality etc.). One of the elements nearly always present seems to be that of social power relationships. The client has financial power over the prostitute, the murderer has power (usually through the use of a weapon) over the murdered, the rapist has physical superiority over his victim and the child abuser has both physical and psychological power over his or her victim. We know that many child abusers were themselves abused as children and so this form of abuse becomes a vicious circle within succeeding generations. In an authoritarian culture like capitalism power relationships are normalised and the family unit often represents a microcosm of this and is where the child first learns of such behaviour. Although the power of parents over their children (derived from either kinship or feelings of ownership) usually keeps them from harm it can also facilitate abuse (dysfunction) and the subsequent fear and resentment within the child can inhibit healthy emotional and social development.

Any contemporary analysis of the origins of the abuse of power in any of its incarnations can only be understood by reference to the authoritarian capitalist context. It would be irrational to single out sick individuals as the cause when the murder of children during war is normalised. Surely the ultimate form of child abuse is to kill them and that would make the likes of George Bush and Tony Blair among the ultimate perpetrators of such a crime.

Socialists despair at the hypocrisy of those who defend war whilst simultaneously exhibiting moral outrage at individual acts of child abuse. There are even some who defend the use of violence (smacking) in their relationship with children. Someone once told me that it was only the fear of his father’s violence that made him aware of the difference between right and wrong; the irony was that he himself was feared because of his own subsequent violent behaviour (perhaps as a result of the familial normalisation of violence). The normalisation of some forms of the abuse of power and the criminalisation of other forms seems completely arbitrary until it’s realised that it is not the specifics of the taboo that matter but only that they exist as a way to enforce conformity and identity within an hierarchical social structure.

There exists, of course, a counter current to the use of taboos for control and that is exemplified in the struggle for personal and therefore sexual liberation. The politicisation of sexuality (spearheaded by feminism) can be understood as the reflection or antithesis of the sexualisation of politics (implicit within authoritarianism in terms of dominant and submissive psychology). Socialists have always supported the liberation from any kind of political and/or personal oppression. Our belief in the potential of our species to create a better world implies both a political and moral historical progression. Unfortunately this demand for liberation is at the moment mainly articulated in terms of individual, gender or racial identities rather than that of class and thus of humanity itself. In some ways this sort of ‘identity politics’ is a kind of consumerism with the perceived right to ownership of the self at its heart – rather than a recognition that the ultimate liberation of the self depends on the liberation of all.

With the confident expectation that a socialist society will immensely minimise (if not completely eradicate) the incidence of abuse, primarily because of the absence of hierarchical institutions, how are socialists to respond to the questions that began this article in the here and now? The forgiveness of some crimes by the victims and by the community would seem to benefit everyone concerned and is certainly preferable to internet ‘witch hunts’. But of all crimes the abuse of the weak by the strong, whether they are children, the elderly or the mentally and physically handicapped, is particularly hard to forgive and certainly should never be forgotten or hidden. The creation of a human community where such behaviour is inconceivable is one of the goals of socialism. Some may think this to be no more than a utopian dream but even as an aspiration it is surely infinitely preferable to pinning medals on pilots who have been responsible for the mangling and killing of children – or the state sanctioned murder of anyone else for that matter.

Would you like someone always by your side, there just to take out any would-be assailants or even take a bullet for you? Fortunately, most of us don’t have the kind of life where we’re likely to need this, even if we were in a position to hire someone. However, it’s different for the senior politicians who have their own personal, steely-faced minders. This is the set-up of BBC1’s blockbuster drama Bodyguard, which features Richard Madden as David Budd, the police protection officer (PPO) assigned to Julia Montague, a Tory Home Secretary. As a bodyguard, Budd’s role is to keep his ‘principal’ safe from dangers such as assassination, theft, kidnapping, violence and harassment. There’s some tension between the two characters as Montague supported military action in the Middle East, and Budd is an ex-soldier haunted by his time fighting there. Inevitably, there’s sexual tension between them as well, although sleeping with their principal presumably isn’t in a bodyguard’s job description.

At least 10.4 million people tuned in to Bodyguard’s first episode, one of whom was Theresa May, although she reportedly switched off after 20 minutes. Writer Jed Mercurio has been behind other hits such as Line Of Duty, Bodies and The Grimleys. His breakthrough came in the mid-‘90s with Cardiac Arrest, which was as much an angry polemic about working conditions in the NHS as it was a drama. He’s always thorough with his research, this time bringing in ex-bodyguards as advisers and basing much of the plot in real-life departments of London’s Metropolitan police. PPOs are part of the Met’s Royalty and Specialist Protection branch (SO1), which provides protection for the royal family, some government officials and visiting heads of state. The police force as a whole is there to defend the status quo, which this department does in a more literal way than most. The Counter Terrorism Command (SO15) works to detect, investigate and prevent terrorist attacks and networks, which in the drama has a fraught relationship with MI5 in uncovering who’s behind the threats.

The culture of the police and politics is depicted as starchy and clinical, with suspicion rather than much warmth between the characters. This is ideal for a thriller, of course, but isn’t the kind of world which seems attractive to work or live in. The inner workings of government, police and security services are likely to be cold and bureaucratic, being there to prop up a divisive, restrictive system. The fact that politicians need bodyguards demonstrates how removed they are from those they are supposed to represent. The threat of attack comes from people or organisations so affected by the system that they are desperate and damaged enough to see violence as the way to respond. Although tactfully not referred to in the drama, it comes only a couple of years after the murder of Labour MP Jo Cox by a far-right loner, and the attack in Westminster by an Islamic extremist. Since then, the process for MPs wanting to make additional security arrangements has been simplified, and they have been offered training in Krav Maga, a type of unarmed combat. A wider effect of this climate is an increase in surveillance, not just of suspects but of everyone. In the drama, the Home Secretary is keen to strengthen the real-life Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000, which covers state powers of surveillance, from undercover officers to bugging to intercepting communications. These days, it takes just a few clicks of a mouse to uncover what anyone has put online, their whereabouts and their movements. Bodyguards are only one part of the state’s security machine.

Bodyguard has a twisty-turny plot which takes us away from what’s recognisable. But how realistic is the series’ basic set-up? In an article in the Mail on Sunday (26 August), ex-PPO to three Foreign Secretaries, Detective Constable Paul Ellis said the programme did ‘a terrific job’ in portraying a bodyguard’s role, adding ‘the relationship between a PPO and their charge, or principal, is fluid in that he or she is not actually your boss – you’re a police officer and as far as security goes, you’re the boss’. Ex-Home Secretary Jacqui Smith said as a Minister she ‘was used to the constant company of aides and officials. But what I had never experienced before was the 24-hour-a-day presence of armed police officers as one of the senior Cabinet Ministers who receive personal protection. … You could hardly make a good drama from the mundane reality of what it’s like to have personal protection. I would have liked to see them try to make a compelling television scene out of the burly protection officer having to make small talk with constituents at a coffee morning’. According to former protection officer Brian Isdale, getting involved so intimately with their principal’s life can mean bodyguards ‘start to adopt the mannerisms of those they are protecting. It’s known as ‘red carpet fever’’ (Guardian, 21 January 2011).

So, being a PPO to a politician is a peculiar relationship, both close and alienating. But then you’d have to be a bit peculiar to be a politician, or someone who would take a bullet for one.

Class war

Next year is the 200th anniversary of the Peterloo Massacre, one of many brutal battles in capitalism's ongoing class war, which saw a peaceful gathering of radicals in Manchester charged by a gentry militia and resulted in 15 deaths and 400-700 non-fatal injuries. Those attending had come to hear Henry Hunt, who advocated parliamentary reform and repeal of the Corn Laws, and carried banners calling for Parliaments Annual, Suffrage Universal, echoes of the French Revolution's Liberty and Fraternity. There was, however, a general lack of political clarity, well illustrated when a band played God Save the King before the meeting started. The Times four days after the slaughter was both candid and clear: 'The more attentively we have considered the relations subsisting between the upper and labouring classes throughout some of the manufacturing districts, the more painful and unfavourable is the construction which we are forced to put upon the events of last Monday...The two great divisions of society there, are the masters, who have reduced the rate of wages; and the workmen, who complain of their masters having done so. Turn the subject as we please, to this complexion it must come at last'. The anniversary is marked early with the release of Peterloo. 'Mike Leigh's period drama has immediacy and a sense of anger. It will ensure that the bloody events in St Peter’s Fields nearly 200 years ago are put back on the radar of politicians, historians and cultural commentators alike' (theindependent.co.uk, 1 September). The film will be released next month, and if it registers with a less exclusive audience, reminding us that the class struggle, which throws up countless victims – from Peterloo to Marikana, Tolpuddle to Gdansk, and Kronstadt to Orgreave – has not gone away, it should be welcomed. The class war will not come to an end until the capitalists are defeated by the workers. That defeat will not require workers to use violence against the bosses – unless, of course, the capitalists have undemocratic ideas about making martyrs of themselves by defying the will of a conscious, socialist majority.

Star wars

The dailycaller.com (31 August) is one of many conservative websites lamenting loudly that a MOVIE ABOUT ONE OF THE MOST ICONIC MOMENTS IN AMERICAN HISTORY DOESN'T FEATURE AMERICAN FLAG. 'The upcoming film about Neil Armstrong’s and Buzz Aldrin’s iconic moonwalk does not feature arguably the most important moment of the entire event. “First Man,” starring Canadian actor Ryan Gosling and directed by Damien Chazelle, does not feature a scene of the American flag being planted on the moon’s surface because Armstrong’s accomplishment “transcended countries and borders,” according to Gosling. “I think this was widely regarded, in the end, as a human achievement [and] that’s how we chose to view it” Gosling argued. “I also think Neil was extremely humble, as were many of these astronauts, and time and time again, he deferred the focus from himself to the 400,000 people who made the mission possible.” “He was reminding everyone that he was just the tip of the iceberg – and that’s not just to be humble, that’s also true.” Gosling continued to say that he doesn’t think “Neil viewed himself as an American hero. From my interviews with his family and people that knew him, it was quite the opposite. And we wanted the film to reflect Neil.”' Hear hear! Worth remembering on the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing next year by those who are amazed and enthralled by the recent space-related discoveries or not is the fact that as long as capitalism remains on Earth, its rockets, its space stations, its whole space technology will be used as a means to solve the problems thrown up in the competitive struggle for markets by the major powers. That is, as the ultimate weapons of war.

Peace on Earth

'The task of creating a coherent and free society is the mightiest to which man has summoned himself, and it is the task which now presses urgently upon us" (Professor G. D. Herron, Why I Am a Socialist, 1900).

'What man has done, the little triumphs of his present state, and all this history we have told, form but the prelude to the things that man has yet to do' (H. G. Wells, A Short History of the World, 1924).

'You, the people, have the power to make this life free and beautiful—to make this life a wonderful adventure' (Charlie Chaplin, The Great Dictator, 1940).